Navigating the Piñones highway to Loíza is like seeing an unrepeatable coast. The palette of blues that borders the sand in changing browns is like vibrating in the Antillean land. It is a privilege for the eyes, an awakening to our own.

I drive observing a panorama that is not new to my eyes, but always knows how to amaze. Enjoying my surroundings I travel in time and I try to keep both hands on the guide because experience has taught me that. There have been multiple collisions with immovable objects, and distracting myself is not an option. So, I bottle up in my imagination the explosion of feelings that I feel inside my heart.

I am going to see Julia Nazario Fuentes: the Mayor of Loíza; a woman who weaves humanitarian networks; counselor of a town that is bubbling with the most intimate of our culture; a five-star professional; and a tireless ally of social justice.

Julia is a force of Antillean nature, and according to the Bible – one of her favorite books – her name means “God’s peace for the weary.” Five letters – two consonants and three vowels, which also honor the memory of the poet Julia de Burgos – another avant-garde woman who immortalizes the Río Grande de Loíza in her literary work. That mysterious iridescent body of water that embraces the entrance to this town like a sentinel. Like an ode to life and its uncertainties.

I smile to myself – it is a miracle that with so many thoughts – I arrived unscathed to the City Hall. Especially because when I crossed the bridge to Loíza, the diplomat in me, effusively greeted the friendly flags waving in a reunion from the window.

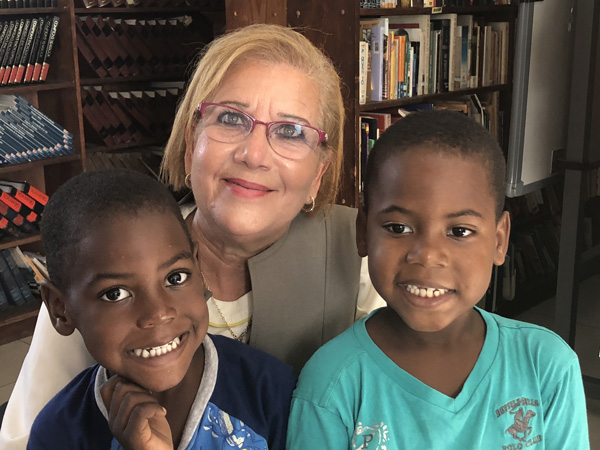

I heard her voice from miles away, and upon identifying her we greeted each other in the hallway. We walked to her office like in the old days. At the time I enjoyed the privilege of being their ally in the same cause: the human rights of our children and youth.

But this morning she had the challenge of capturing a legendary life.

Julia tells me that when she was six years old her father was murdered in the frozen streets of New York, the city where she lived part of her childhood. And, her family, like millions of others classified as immigrants, went north in search of possibilities. In her case with a passport of peculiar idiosyncrasy. She was and was not a citizen of a giant country. New York and the murder of her father were sealed in her memory like a gloomy iceberg until her adolescence.

She returned with her mother and sister to Puerto Rico and grew in duality with herself. On the one hand, she recognized the greatness of a fighting mother, on the other she resented her absence in a time of survival. For a time, Julia blamed her father’s murder on her mother until she found respite by delving into Bible studies. The Bible, she says with her sky-blue eyes, was “my anchor” in moments when, suffering from the challenge of growing up is a certain etymology of the word adolescence.

Julia read the Bible with her older sister and later did Bible studies. At 14, she was elected President of the Youth Congress of Puerto Rico of the Universal Church. That leadership, capturing youth with her charisma, remains with her forever. Julia subconsciously transformed the absence of a father into an open path.

She began to see her mother differently and her gaze softened – she admired her tireless work as an assistant to the Mayor of Canóvanas and her discipline as a member of the Popular Democratic Party. In fact, in the era when politicians did not have social networks, and they campaigned – house by house, she knew that Don Rafael Hernández Colón was about to arrive at her home when she saw the poppy blanket on the living room sofa. The flowery blanket predicted a time to recharge – it was the headquarters where the Governor rested between door-to-door visits.

Nap, Coffee, Thank You, Hugs and Keep Walking.

Julia tells the anecdote as a chapter of Puerto Rican magical realism. Poppies (I later investigated out of botanical curiosity) are known as the flower of consolation. So the consolation of others has always been her family’s too. Perhaps her community roots, her unique empathy, lie in those experiences.

When her mother dies, both were already in a truce, but a few months later her uncle is killed. The iceberg, the memory of the murder, revives her in the hot climate of Puerto Rico. But she must continue on her way.

With outstanding grades she enters the University of Puerto Rico – but she is in a hurry and wants to escape. She studies commerce, gets a job to support herself and gets married. That love was like a wave, it came and went. She suffered and at the same time learned to love herself more.

She ends the cycle of fruitless love and returns to the University like a good little chicken. Espuela finishes a Master’s degree in Guidance and Counseling with a specialty in addictions. This knowledge allows her – later in her life – to help a loved one and overcome addiction. She also succeeds in the academic world when she decides to do a Doctorate and obtains High Honors. Julia is a woman of laurels, determined, persistent and persevering. She is also a survivor of a double mastectomy and for whom feeling mutilated was never an option.

Yearning for the evolution of her country, Julia decides to work in the Department of Education. She knows the complexities of the system from the inside, collaborates with several governorships, but is dismissed in one of the changes of administration.

“That was a very hard blow. They marked us for life.”

However, she does not give up and gets a job providing services to vulnerable populations. She writes her thesis with the goal of bridging the gap between students left behind by the vicissitudes of life. At the same time, she returns to work in the Department of Education where she holds various leadership positions.

With education as the foundation for the progress of her people, Julia enters politics. She makes history by becoming the first woman to occupy the Loíza seat after 44 years of dominance by the statehood party. Today Julia continues to defend her town from stigma, discrimination and demoralization. Running for a third term was not in her plans, but after the ravages of Hurricane Maria and the ravages of the pandemic, the rebirth of Loíza is her priority.

Her husband, Felix Algarin, a businessman and lifelong ally, always supports her. Julia confesses that she would have liked to be Secretary of Education, but that dream will remain in the future of others. Her commitment to Loíza is unbreakable. She tells me that she has written a book and is planning the second. We talk in time without time, and the cell phone begins to vibrate on her desk like a little grasshopper.

We say goodbye with a tight hug – and out of the corner of my eye I notice on her desk: a black boy, a small sculpture of a guaraguao and a poster that reads: Loíza blooms green brown. That is Julia – a green woman. Green of hope and brown earth, with deep roots, brave steps, knowing how to get down to the mud and work insatiably.

He asked her what her favorite books were: Don Quixote and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

“Bibiana, the madness of Don Quixote is life itself,” and with that quote in mind I once again traveled across the Loíza bridge on wheels, observing the Río Grande de Loíza and its flags waving the wisdom of a woman who lives Peace in her Courage