Eddie Ferraioli is a man of hugs, a multi-colored heart, and creative luminosity.

My father’s first cousin and the youngest of three children, his last name “lost” the U at the Immigration Registry Office when his father emigrated from Italy to Ponce, Puerto Rico.

He grew up in a home with European discipline—arranged between an Italian father and a German mother. For all, sports, work, and the arts were essential to acquiring life skills.

Eddie, despite dutifully completing his homework assignments, had in his DNA an anxiety with no explainable origin that resided in his biology.

An energy that ran like a short circuit inside him.

Without realizing it, living in a wave of blues and breezes was his shore—his creative nature.

He well remembers that from the age of seven, nerves ate away at him—speaking in public, digesting food well, socializing, or competing in sports were synonymous with “the end of the world.”

It was such an uncontrollable feeling that he required medication from an early age. He says this bluntly, deeply convinced that the taboos surrounding mental health lead to major consequences. His father, a doctor, and his mother were pioneers. They accepted and supported him.

Recreational swimming was literally his lifeline. Feeling like a fish both in pools and in the ocean calmed his racing mind. Likewise, the solidarity with his siblings, Mayita and Joey; the literary world; writing freely and enjoying the music of Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones—were essential tools in his emotional development.

With tenacity and discipline, Eddie finished high school. After graduating, he attended Iona College for two years, a small university where he progressed academically, but he retreated to protect himself. He claims these confinements served as evolutionary explorations. They helped him understand himself like an X-ray.

But he had a long period of time, where writing ceased to be a light. He felt compelled to take a break when, “I ran out of words and my ideas faded.” He accepted the emptiness, and recounts that those gray shadows, that drought, marked an era of his development.

Pause and Smile.

Because when he was sheltered in shadows, an inner whisper always murmured, assuring him that his cave had an exit. “I think it was hope, speaking to me.” Nevertheless, returning from the United States to Puerto Rico to finish his high school diploma was the sensible course.

Between university summers, he traveled to Europe—to the continent of his four entangled roots: Italian, Puerto Rican, German, and Jewish. And, coincidentally, at the Church of Notre Dame in Paris, he found his path.

He emphasizes: “Bibiana, I don’t know if the anecdote is real or imagined, but in the church I met a hunchback. He asked me for alms and had coins. We walked inside and saw the stained-glass window of the Rosette. I interpreted it as a sign.”

Awestruck by the majesty of glass art, Eddie remembers the beautiful stained-glass windows in a relative’s house. He felt the uncertainties floating in his mind calm down. He anchored himself on a new shore.

He felt his purpose and recognized himself as an artist.

After visiting Europe, he returned to Puerto Rico to study a postgraduate degree in psychology, but when one of the requirements was public speaking, he dropped out. He spoke with his mother and, in addition to continuing with stained-glass art, decided that a master’s degree in special education was appropriate.

In the world of neurodiversity, he met his wife, who was studying speech pathology. He fell in love, and they married. He was always certain that having children wasn’t an option for him—because he deeply cared about his mental health. They both embraced that truth.

Shortly after they were married, his wife was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Her condition “gave me perspective on my condition and made me become the anchor.” Today he is a widower.

He cherishes his achievement with nostalgia and shyly acknowledges that it was a bastion of unconditional love. He cared for Mari until her death, and for both of them, stained-glass art was a shared path, a collective therapy.

Today she is gone, but art survives her. It was Mari and his psychiatrist who encouraged him to hold his first exhibition at the age of 52. He had eight weeks to be brave.

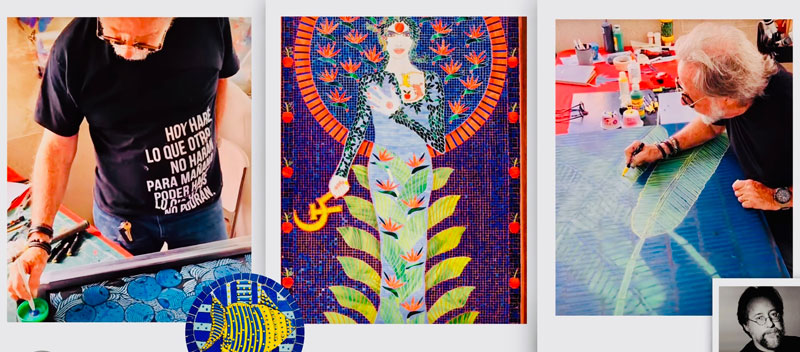

In front of an audience, he was able to speak about his art, his process, and how he is a mirror of his stained-glass windows, of his emotions. That exhibition was at the Museo de Arte de Ponce—and today, he has spent more than a decade building his imagination in a range of arts.

His art dazzles both at the Hotel El Oso in Spain and at the Stella Maris Parish. Likewise, in recycled windows of Old San Juan with mosaics of native fruits; in the shared exhibition with his nephew; or in the Quixotic Goddesses that are a tribute to women who survive violence.

This spring, he returned to the sea with his art. With renewed vitality. Along with young university students from the Community Architecture Workshop (led by Professor Martínez-Joffre), he carried mosaics of marine fauna to place on the seabed near the Escambrón.

“Unfortunately, they were stolen, but I trust they will return to the water, to the marine museum.” He says this with passion and certainty.

I feel, we feel gratitude. The family discussion has been a fascinating journey. The spiritual coffee has flown like the breeze. It’s time to continue working. To continue building art in dreams.

We say goodbye. After more than seven decades of life, I see a European Puerto Rican, an artist of the world. But above all, a man anchored in a miraculous art.

An art that transports you and transports us to humanity.